Chrome has long been the main reference in the segment of web browsers, but Mozilla engineers have never thrown in the towel, and in fact months ago prepare Firefox Quantum, the version with which they believe that they can finally turn it around to the tortilla.

This new browser starts its journey with Firefox 57, a version that is finally available in the channel for developers and anyone can try. The changes are important on the outside and inside, and we have been testing it for a while thanks to the ‘nightly’, the preliminary versions. These are our first impressions on a Firefox that is, above all, faster.

Firefox is faster because it works in parallel

That is what you will notice when opening new navigation tabs, which according to those responsible open twice as fast as they did a year ago, when Firefox appeared 52.

One of the main reasons for this speed improvement is Servo, the new rendering engine developed in the Rust programming language that has a fundamental difference with its predecessor: it takes advantage of all the processor cores of your processor.

In previous versions of Firefox the rendering engine focused all its activity in a single core, but Servo changes the focus and if you have more than one core in your processor (something usual in both desktop or laptop as in CPUs for mobile devices), Servo will work in parallel in those cores, distributing the load so that all those cores contribute to the performance.

Do you notice that improvement? Definitely. The tests of the own Mozilla with Speedometer demonstrate it, and the sensations when using the navigator confirm that improvement in speed. Maybe it’s not such a dramatic improvement as the data from Mozilla itself, and especially if one comes from Chrome the differences are more difficult to appreciate, but the truth is that everything loads really fast.

A browser that behaves almost like an operating system

Another of the fundamental internal changes in the new internal design of Firefox is its management of the navigation: until now the management of the different navigation tabs that we were opening was treated as a single process, something that Chrome understood that it should not be done this way.

Those responsible for Google were pioneers in converting each tab (and extension) into a process, which allowed to separate from each other, isolate and manage them independently.

In Firefox they had been pursuing that same objective for some time, but as their managers explained, adapting to this type of operation would make it necessary “to stop supporting extensions and complements that were precisely dependent on the single process architecture”.

Mozilla was reluctant to make the change because the extensions were precisely one of the navigator’s strengths, and that’s why the work was divided into two different areas. The first, the Electrolysis project, responsible for making Firefox support multiprocessing. The second, a difficult transition from the traditional architecture of the extensions to the calls WebExtensions.

Electrolysis was launched for the first time in August 2016, but with the new version included in Firefox Quantum the thing has gone to more, and now has expanded the number of processes that Firefox uses to process and protect the content of each web page, in addition to improving the management of these processes to improve the use of memory, performance and stability. Not only that: each of these processes can work in several processor cores at the same time (the parallelism we talked about), which improves performance and protects those browser tabs against possible “crashes” of other tabs.

Unlike Chrome, of course, tab management does not create a process for each tab – something that does not help memory consumption precisely – but in Firefox four separate processes are created for the content of web pages, but they are not created more, and as we open tabs these four processes are reused, something that does not seem to compromise speed and that above all helps control memory consumption.

What is the result at a practical level? The fact that Firefox actually has a really remarkable memory management that stands out against Chrome especially with a large number of tabs open. The load on the system is lower, which means that you can open more tabs with the same amount of RAM – there are extreme cases like the 1650 open tabs we were talking about recently – and in doing so you will notice how the impact is not so serious in Firefox as in Chrome.

This can be especially important in mobile devices, although it is also true that we do not usually open as many tabs as in a browsing session on a PC or laptop.

A new “square” design with Photon as the protagonist

To these numerous and important internal changes are added external changes. The user interface of Firefox changes radically with decisions that have not convinced me personally. At least, still.

To begin with, the eyelashes no longer have those elegant curved corners to become pure and hard rectangles. Tougher and less showy, Mozilla’s obsession seems to have been focused on saving vertical space.

There is no “air” above those tabs, although we can add it by activating the title bar (which does not help much, really) or by adding some extra space by activating the “Drag space” box of the “Customize” option of the Firefox menu.

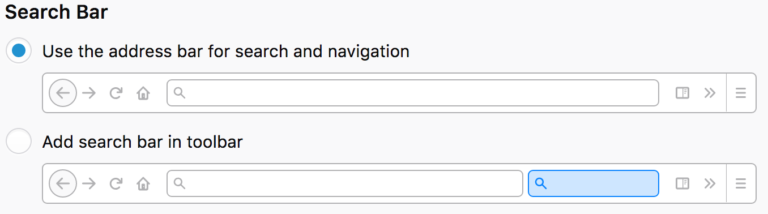

Another radical change will receive a warm welcome from traditional Chrome users. Firefox finally (finally!) Unifies the address bar and the search bar, thus copying the behavior of the glorious (at least, in my opinion) Chrome Omnibar.

Users who wish to do so can separate both options (again through the Customize menu), but being able to perform both searches and entering new URLs from the same site -something Mozilla talked about in June of 2017- seems to me one of the successes most important of that change in the interface.

You may also like to read: Edge vs Chrome is it time for change?

It also changes the Firefox drop-down menu, the iconography and its position (the reload button is placed next to the backwards or forwards in the navigation (Hallelujah!) And the organization of the options. , next to the download, allows you to manage this as well as other sections such as bookmarks, history or a new option to easily take screenshots of navigation.

But as we say that new drop-down menu on the right side stops showing a series of large icons to move to a list of options that goes “to the point” and is more aligned with what other browsers and applications often do. It’s less visual, but it probably helps the speed with which we access those options. Personally I do believe that the previous menu interface differentiated Firefox and was an attractive aspect of the user experience, but it is true that this change helps with that familiarity we already have with drop-down menus in that format.

I have not been comfortable with this obsession with this vertical space saving – especially now that our monitors have more resolution than ever, also in the vertical, something that is noticeable if we use a bookmark bar, as is my case.

That bar seems to be “squeezed” between the address / search bar and the beginning of the content: there are no spaces, and those permanent markers seem too boxed. Giving them some air would not have been more. Here there is likely to be relief in the traditional support of themes and templates that allow changing the appearance of the browser, although here we will have to investigate something else to see if personalization can effectively solve these small personal criticisms and those that may have other users.

Where is my extension?

In August 2015, Mozilla explained its action plan for add-ons or extensions. The WebExtensions made use of a new API largely compatible with Chrome and Opera, which would make it easier to develop those add-ons for several browsers at the same time.

Among the requirements was the support of the new multiprocess architecture of Firefox so that these extensions could work. The old (legacy) have been supported for some time in previous versions of Firefox, but that changes with Firefox Quantum (Firefox 57), the browser that gives the exclusive jump to the WebExtensions.

What does that mean? Well, extension developers have the responsibility of having modified their add-ons to become WebExtensions. The change, even having been announced no less than two years ago, is so important that there are still a good number of add-ons or extensions that are still not available except in the legacy version.

That implies that we can not use them in Firefox Quantum, something that can cause more or less important annoyances. In my case I found one or another that used to use in previous versions of Firefox or Chrome and had no alternative in Firefox Quantum, and it is likely that the same thing happens when you make the jump.

It can, in fact, that some of those “legacy” extensions never make the leap to WebExtensions, which of course ends up being quite disappointing. Given that the vast majority are developed and managed by independent developers who programmed them in the past but no longer take care of them, the truth is that this situation is logical and should be acceptable. That does not mean, however, that one feels that this change to Firefox Quantum has problems that may be more or less serious.

Firefox Quantum, conclusions

This approach to Firefox Quantum (Firefox 57) in the ‘nightly’ versions of development and in the current version of the developer channel has served to verify that the revolution posed by those responsible for Mozilla is of course interesting.

The benefits seem to be evident in the field of speed and fluidity of browsing sessions , something that is especially noticeable against previous versions of Firefox. The differences with Chrome – I have not tried other browsers for lack of time – are hardly noticeable, and in fact my feeling is that certain pages continue to load faster in Chrome, while others seem to do better in Firefox Quantum.

Mozilla has done well to focus on that battle, because users do not seem to take too much into account the fact that the protection of privacy is one of the values of Firefox. Here the sensations do not work: everything you do in Chrome applications and services ends up being part of your dantesic data collection business (whatever they may be), while in Mozilla that appetite for our data does not exist (or at least not it’s so obvious) because while Google lives from that data, Mozilla does not.

That is another of the fundamental factors for which we live somewhat concerned about this constant transfer of privacy, and in fact is the reason that despite how well it works Chrome (and other browsers), some have returned to Firefox for weather.

Whether you care about privacy or not, one thing is certain: Firefox Quantum means that the jump can no longer be justified by the “purity” of this Open Source development – I almost forgot, you have all the code in MDN -. It is true that Chrome is based on another Open Source project, Chromium, but be careful because the differences between one and the other are obvious.

So, well for Firefox, a browser with which at least I feel better surfing the Internet, and now it is faster and more efficient than ever. That maybe is what they really needed in Mozilla to convince the whole world that this browser, of course, cool.